Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio & His Era

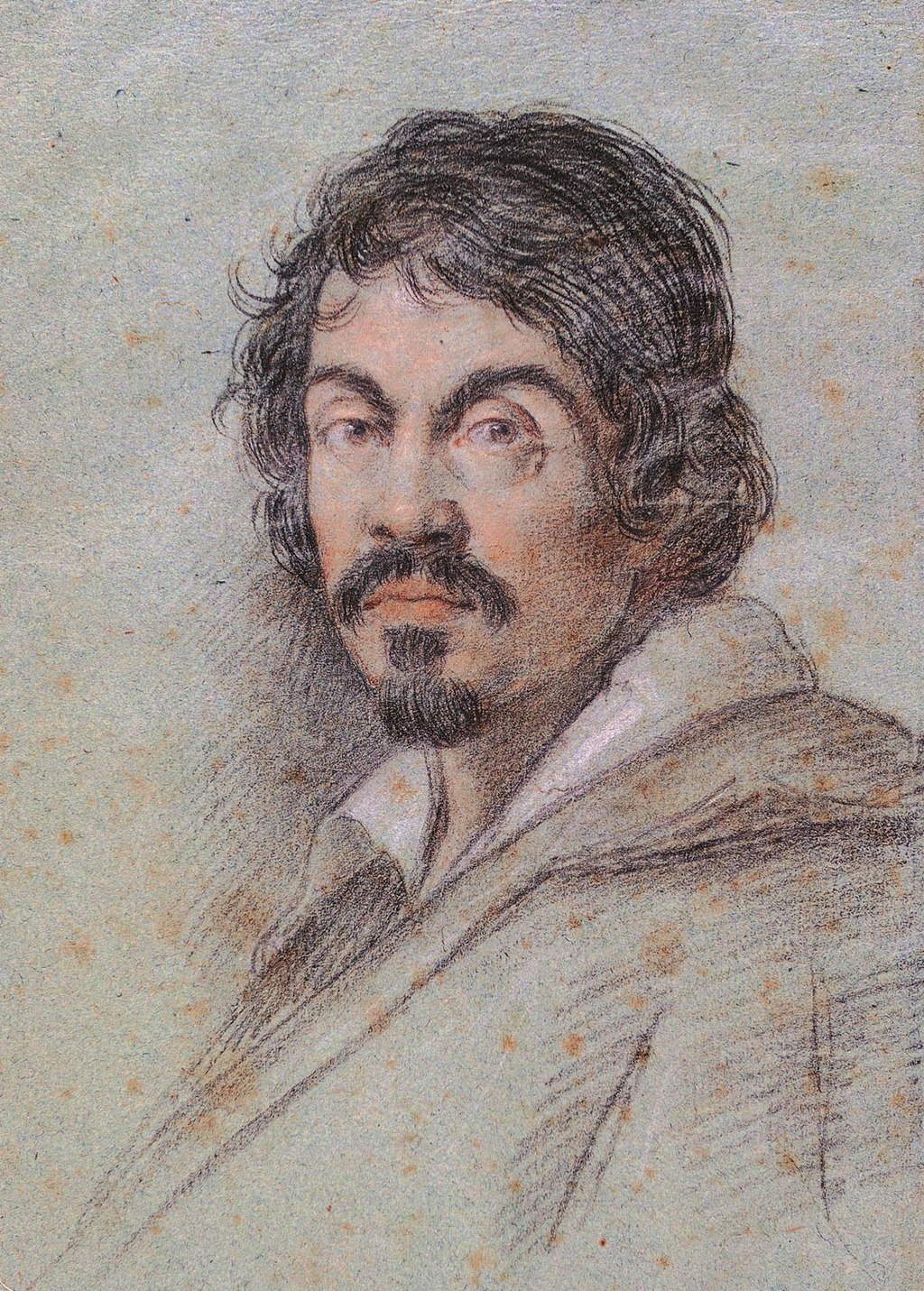

Known simply as Caravaggio, emerged as one of the most influential artists during the Baroque period. Born in 1571 in Milan, Caravaggio’s formative years were imprinted by the late Renaissance era’s artistic advancements. Moving to Rome in his early twenties, he entered a city that was the epicentre of political, cultural, and religious transformations.

Baroque Quest for Realism

Baroque art, flourishing from the late 16th century to the early 18th century, sought to evoke emotion through dramatic realism and intensive detail. Caravaggio differentiated himself with his chiaroscuro technique, which contrasted light and dark to emphasise depth and volume. His approach captured raw human emotions, making each painting a vivid narrative.

Social and Political Context

During Caravaggio’s time, Rome was under the powerful influence of the Catholic Church, which commissioned artworks to convey religious themes amidst the Counter-Reformation. The church aimed to reaffirm its authority against Protestant Reformation ideals. As a result, demanded artworks often depicted biblical scenes and moral stories designed to resonate with the populace.

Caravaggio’s Unique Style

Caravaggio’s works were starkly realist, portraying sacred subjects with lifelike human figures set in contemporary settings. He rejected traditional idealism for a grittier, more tangible representation of divine scenes, often using ordinary people as models. His unapologetic authenticity sometimes invited criticism and controversy.

Personal Turmoil

Caravaggio’s life was as tumultuous as his art. He was known for his volatile temper and frequent run-ins with the law. His personal escapades and short temper often resulted in violent brawls, contributing to an unstable career. Despite these disruptions, his work remained extraordinarily impactful.

Influence and Legacy

Artistic Influence: Caravaggio’s methods profoundly influenced contemporaries and future generations, such as Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt.

Cultural Impact: His works bridged the gap between the Renaissance’s idealism and the emotional realism of the Baroque era, leaving a lasting imprint on modern art.

Key Works

- The Calling of Saint Matthew: This painting exemplifies his use of chiaroscuro.

- Judith Beheading Holofernes: Demonstrates his ability to convey intense emotion and action.

- Supper at Emmaus: A piece that beautifully merges the spiritual and the mundane. Caravaggio’s era was an interplay of artistic innovation and societal transformation, which he captured expertly through his radical and evocative paintings.

The Role of Light and Shadow in Caravaggio’s Work

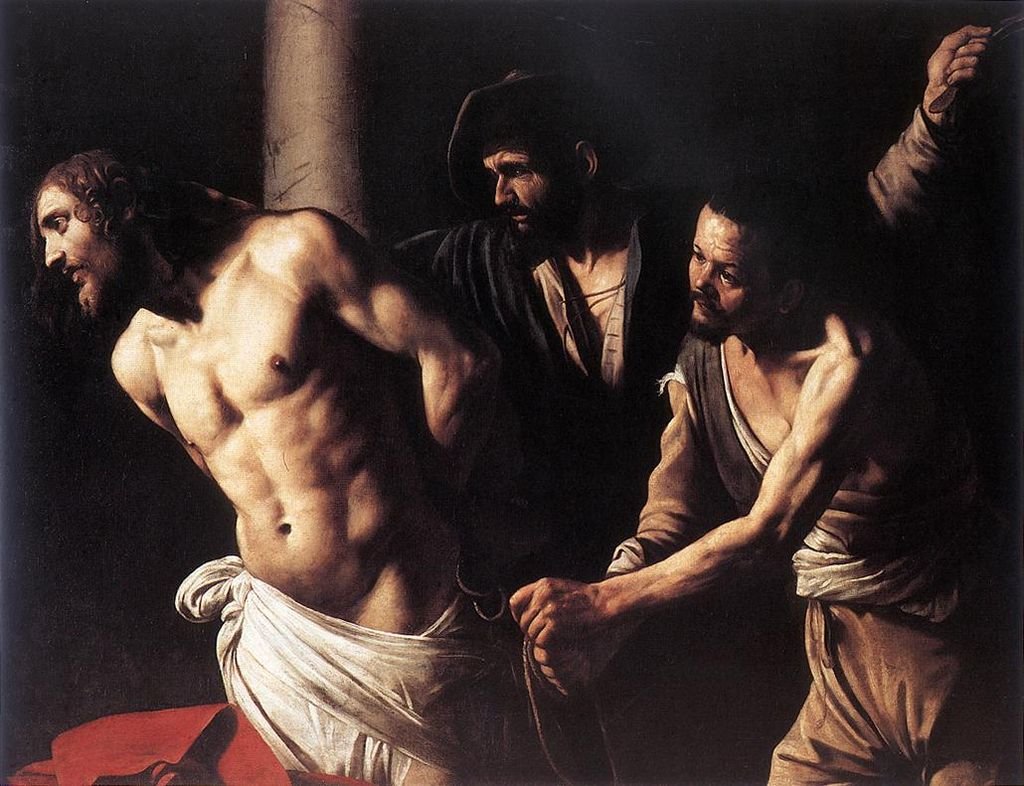

The interplay between light and shadow in Caravaggio’s paintings is a defining feature of his artistic style. Often referred to as chiaroscuro, this technique emphasises the stark contrast between light and dark, drawing the viewer’s eye to specific elements within the composition. Caravaggio uses this method not merely for dramatic effect, but to imbue his work with deeper symbolic meaning.

Highlighting Focal Points: Caravaggio often bathes central figures in his compositions with a dramatic beam of light, making them stand out against a much darker background. This spotlit effect creates a natural focal point, guiding the viewer to interpret the primary subject or action of the scene.

Emotional Depth: The strong contrast between light and shadow conveys intense emotional states. Light typically represents revelation, hope, or divine presence. Conversely, the shadows often evoke secrecy, ignorance, or internal conflict. Through this chiaroscuro technique, Caravaggio adds a layer of psychological complexity to his narrative.

Religious Symbolism: In many of his religious paintings, such as “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” the light source is symbolic of divine intervention. The light breaking into otherwise darkened settings serves to underscore moments of spiritual epiphany or transformation. The shadows represent the worldly and the temporal, highlighting the divine light’s power to penetrate and redeem.

Realism and Grit: Caravaggio’s use of tenebrism—a heightened form of chiaroscuro—gives his scenes a sense of realism and immediacy. The deep shadows ground his often divine or mythological subjects in the real, tangible world. This technique helps to bridge the divine and the everyday, making the holy scenes more accessible to the viewer.

Dramatic Narrative: Light and shadow are key in creating a narrative tension within Caravaggio’s works. By obscuring certain elements and illuminating others, he builds a visual story that unfolds gradually as the viewer’s eye adjusts. This dynamic interplay captures moments of action, heightening the dramatic impact.

The masterful manipulation of light and shadow not only defines the physical space within his compositions but also amplifies the emotional and symbolic weight of each scene. Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro continues to influence the realm of visual arts, demonstrating how light and shadow can transcend mere technique to become a powerful vehicle for storytelling.

Religious Symbolism in Caravaggio’s Paintings

Caravaggio’s works are renowned for their vivid use of religious themes and symbols. His paintings often reflect deep theological insights and spiritual messages. Caravaggio expertly merges biblical narratives with symbolic elements, offering viewers layers of meaning and contemplation.

Use of Light and Shadow

Chiaroscuro: Caravaggio’s distinctive use of light and shadow, known as chiaroscuro, symbolises the eternal struggle between good and evil, divine illumination versus human darkness. The stark contrasts often highlight moments of spiritual revelation or conflict.

Depiction of Saints and Martyrs

Martyrdoms: His paintings of saints, such as “The Martyrdom of St. Matthew,” use visual symbolism to highlight themes of sacrifice and divine grace. Objects like the palm frond or a martyr’s instruments underscore their divine calling.

Tenebrism

Darkness: Employing tenebrism more profoundly than just shadows, Caravaggio’s extensive use of dark backgrounds focuses attention on the human subjects, suggesting both their earthly trials and divine significance.

Expression of Human Emotion

Realism: Human expressions in his works often denote spiritual agony, ecstasy, or revelation, as seen in “The Supper at Emmaus.” This emotional depth serves to make the divine more relatable and immediate to viewers.

Symbolic Objects

Everyday items: Caravaggio incorporates everyday objects imbued with symbolic meaning. For example, fruits or the broken bread in “Supper at Emmaus” can signify Eucharistic and resurrection themes.

Caravaggio’s Religious Controversies

Sacrilege: His realistic portrayal sometimes stirred controversy, as in “Death of the Virgin,” where he depicted the Virgin Mary’s death in an unidealised, human manner, displaying a profound and gritty spirituality.

Divine Encounter Portrayals

The Conversion of St. Paul: Highlighting critical spiritual transformations, Caravaggio’s “The Conversion of St. Paul” uses the falling figure of Paul and the celestial light to signify a divine encounter, transformation, and redemption.

Symbols of Purity and Corruption

Allegorical imagery: Pomegranates, wine, and other symbols are often used to contrast purity and sin, summarised perfectly in “Bacchus,” where the fruit’s freshness clashes with its decayed form.

Caravaggio’s religious symbolism serves not only as theological reflection but also as a critique and an engagement with the spiritual crises of his time.

Mythological References and Their Meanings

Caravaggio’s use of mythological references enriches his paintings, embedding them with deeper layers of meaning.

Gods and Goddesses

Apollo

Often depicted with a lyre, Apollo symbolises light, music, and prophecy. In Caravaggio’s works, Apollo’s appearance indicates themes of enlightenment and artistic inspiration.

Bacchus

Known as the god of wine, Bacchus embodies themes of revelry, excess, and the duality of pleasure and suffering. Caravaggio’s “Bacchus” juxtaposes youthful beauty with hints of decay, suggesting the fleeting nature of indulgence.

Mythological Figures

Medusa

The depiction of Medusa, with her snake-laden hair, is not just a symbol of terror but also a reflection on the concept of transformation and protection. Caravaggio’s “Medusa” captures a moment of frozen horror, embodying the power of the gaze.

Narcissus

The myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his reflection, serves as a cautionary tale about vanity and self-obsession. Caravaggio’s interpretation explores themes of self-identity and the existential examination of one’s own soul.

Allegorical Symbols

Labyrinths

Representing both the journey and the quest for knowledge, labyrinths in Caravaggio’s paintings underscore the complexity of human experience and the search for truth.

Shields and Armour

Often symbolising protection and warfare, these elements can also represent the internal struggle and the defence mechanisms of the human psyche.

The Role of Animals

Serpents

Frequently embodying evil or danger, serpents also signify knowledge and transformation. Caravaggio’s inclusion of serpents can denote treachery or the shedding of old selves.

Lions

As symbols of strength and courage, lions in Caravaggio’s works often foreground themes of power and dominance, as well as kingship and nobility.

Natural Elements

Rivers and Waters

Symbolising life, purification, and change, water elements in Caravaggio’s paintings often highlight themes of renewal and the passage of time.

Trees and Foliage

Representing growth and natural cycles, trees and plants in his artwork underscore themes of life, death, and rebirth. By exploring these mythological references and their meanings, viewers gain a deeper understanding of Caravaggio’s complex visual narratives. These elements are not merely decorative; they are essential to grasping the full scope of his artistic expression.

Analysing Iconography: Key Symbols in Caravaggio’s Art

In Caravaggio’s paintings, viewers often encounter a rich tapestry of symbols that convey complex narratives and deeper meanings. Understanding these key symbols is crucial for decoding his artworks.

Common Symbols in Caravaggio’s Paintings

Light and Shadow

Chiaroscuro: Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro, which contrasts light and dark, serves more than a dramatic visual effect. It often highlights the spiritual divide between the holy and profane.

Divine Light: Light frequently symbolises divine presence or revelation, illuminating subjects in moments of spiritual epiphany.

Flowers and Plants

Rose: Generally symbolises love and beauty; when wilted, it can represent the fleeting nature of life.

Fruit: Grapes often indicate abundance and the Eucharist, while a basket of assorted fruits might symbolise various virtues or the bounty of nature.

Animals

Birds: Birds often represent the souls or messengers between heaven and earth. A dead bird might hint at lost innocence or martyred saints.

Snakes: Symbolise evil or sin, often appearing in scenes involving corruption or deceit.

Objects and Artefacts

Skull: A common symbol of memento mori, the skull serves as a reminder of mortality and the inevitability of death.

Mirror: Reflects themes of vanity, truth, and self-examination, often challenging the viewer to consider deeper truths.

Human Gestures and Expressions

Hands: The positioning of hands can reveal volumes; hands in prayer denote piety, while outstretched hands might imply a plea for mercy or divine aid.

Expressions: Facial expressions are meticulously crafted to convey intense emotions, guiding the viewer’s interpretation of the scene.

Biblical References and Their Importance

Saints and Martyrs: Many of Caravaggio’s paintings feature saints, whose symbols and attributes—such as Saint Peter’s keys or Saint Catherine’s wheel—serve to identify them and underline their stories.

Christ’s Passion: The Passion of Christ is a recurring theme; symbols such as the cross, crown of thorns, or nails provide insights into the artwork’s spiritual underpinnings and theological implications.

Contradictions and Dualities

Life and Death: Caravaggio often juxtaposes elements of life and death within a single composition, prompting existential reflections.

Virtue and Vice: The coexistence of virtue and vice within his works creates a moral tension, encouraging viewers to discern deeper meanings behind the depicted actions.

Cultural and Historical Context

Religious Symbols: Rooted in the socio-religious context of 16th-17th century Italy, Caravaggio’s symbols are best understood against the backdrop of Counter-Reformation ideals and Catholic iconography.

Classical References: Incorporates classical mythology and Renaissance humanism, enriching the interpretative layers of his art.

In summary, Caravaggio’s iconography intertwines biblical, classical, and contemporary symbols to create multi-dimensional narratives, making his artwork profoundly rich and complex.

Caravaggio’s Use of Realism to Convey Symbolic Narratives

Caravaggio’s innovative approach to realism broke away from the idealised depictions common in Renaissance art, grounding his works in emotionally intense and physically tangible realities. His ability to infuse everyday scenes with profound symbolic meaning continues to fascinate and instruct art historians and enthusiasts.

Techniques in Realism

Chiaroscuro: Caravaggio’s pioneering use of chiaroscuro, the dramatic contrast between light and dark, added a three-dimensional quality and heightened emotional intensity. This technique not only created a visually striking composition but also provided a metaphorical framework where light often symbolises divine presence or truth, and darkness conveys human frailty or moral ambiguity.

Lifelike Posing: By selecting ordinary people as models, Caravaggio infused his religious subjects with a relatable humanness. The visceral expressions and realistic physical imperfections made the divine stories more accessible and emotionally engaging.

Textural Details: The meticulous attention to textures, from rough burlap to the glistening sheen of sweat or blood, further anchored his scenes in the realism of everyday life. Such detail serves to underscore the grittiness of human existence while still imbuing the work with deeper meaning.

Iconographic Elements

Symbolic Objects: Caravaggio often included common objects imbued with symbolic significance. In “The Supper at Emmaus,” the fruit basket teeters on the edge of the table, suggesting the precarity of human life and the imminent recognition of the divine.

Human Figure and Gaze: The artist skilfully used the direction of a subject’s gaze or posture to guide the viewer’s understanding. In “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” the subtle gesture of Christ’s hand, mirrored by the beam of light, directs attention to Matthew, symbolising divine selection and awakening.

Emotional Depth and Meaning

Caravaggio’s pieces thrive on their ability to evoke intense emotional responses and multifaceted interpretations. Realism served not just as an aesthetic choice but to support the narrative depth. His focus on raw human emotion, from grief to ecstasy, invites viewers to explore the underlying theological and existential questions.

Pathos and Empathy: By focusing on the raw, unfiltered emotion of his subjects, Caravaggio engages viewers’ empathy, drawing them deeper into the narrative.

Narrative Complexity: Each figure in a Caravaggio painting often contributes to layers of meaning, challenging viewers to piece together the symbolic narrative from visual clues.

Caravaggio’s mastery of realism did not merely reproduce scenes from life but augmented them to relay complex, often multi-layered stories filled with spiritual and moral contemplation.

Interpreting the Emotions and Expressions of Figures

Caravaggio’s mastery in portraying human emotions adds significant depth to his works. Each expression and physical gesture serves a purpose, conveying an underlying message or emotion. Understanding these nuances is key to deciphering the deeper symbolism encapsulated in his paintings.

Facial Expressions

Sorrow and Grief: Caravaggio often uses downcast eyes, furrowed brows, and slightly open mouths to indicate sadness or mourning.

Joy and Ecstasy: Luminous eyes, upward gazes, and subtly smiling lips frequently denote moments of divine joy or spiritual ecstasy.

Fear and Anguish: Wide eyes, tense foreheads, and open mouths can analyse as symbols of fear, distress, or impending doom.

Gestural Language

Outstretched Hands: Hands reaching out or pointing signify pleading, desperation, or the act of divine intervention.

Clutching a Chest: This gesture can indicate deep personal reflection, emotional pain, or a heart-wrenching revelation.

Bent Knees: Submissive body positions, such as kneeling, often represent humility, supplication, or defeat.

Group Dynamics

Intimate Clusters: Tight groupings of figures might symbolise unity, shared purpose, or collective grief.

Isolated Figures: Figures separated from the group often represent alienation, personal reflection, or solitary suffering.

Mirroring Movements: Repeated gestures or expressions among figures can signify shared fate, mutual understanding, or parallel experiences.

Symbolic Colour Use

Warm Tones: Caravaggio often employs warm colours like reds and oranges to convey passion, intensity, or violence.

Cool Hues: Blues and greys can indicate tranquillity, calmness, or sombreness.

Chiaroscuro Contrast: The stark contrast between light and dark not only adds drama but also symbolises the struggle between good and evil, revelation and concealment.

Realism and Naturalism

Caravaggio’s attention to realistic detail enhances the portrayal of genuine human emotion. His use of real models, capturing individual character and imperfection, adds to the authenticity of his subjects’ expressions. This naturalism engages viewers on a visceral level, making the emotional content of the scene palpable and relatable.

Interpreting the emotions and expressions in Caravaggio’s paintings provides an insightful window into the complex human condition. His nuanced portrayal of feelings and interactions encourages viewers to delve deeper into the narrative and emotional undercurrents of each scene.

Impact of Caravaggio’s Personal Life on His Symbolism

Caravaggio’s tumultuous personal life influenced his symbolic use of light and shadow, resulting in a dramatic chiaroscuro technique. His biographical details reveal a volatile personality, deeply impacting his work. Certain symbolic elements evident in his paintings may directly reflect his experiences and psyche.

Persona and Symbolism

Violence:

Caravaggio’s frequent altercations and confrontations are echoed in the violent themes of many of his paintings. Works like “Judith Beheading Holofernes” and “The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew” illustrate a raw intensity, possibly rooted in his own brushes with aggression.

Flight and Exile:

Periods of escape due to legal troubles, including murder accusations, might have intensified his themes of turmoil and unrest. Painful experiences of solitude and displacement are mirrored in works such as “Rest on the Flight into Egypt.”

Spiritual Struggle:

Caravaggio’s ambiguous relationship with religion, marked by both devotion and defiance, permeates his artwork. Paintings like “The Calling of Saint Matthew” and “The Conversion of Saint Paul” depict profound moments of spiritual revelation and tension.

Symbolic Elements

Light and Darkness:

Caravaggio’s controlled use of light, often illuminating stark truths, contrasts with enveloping shadows, symbolising inner moral conflicts. This dramatic use of chiaroscuro not only heightens emotional intensity but may reflect Caravaggio’s own dichotomies.

Objects as Personal Symbols

Swords and Weapons:

Frequently present in his work, weapons could symbolise Caravaggio’s violent tendencies and turbulent lifestyle.

Wine and Food:

Depicted in a raw, realistic manner, these elements might signify both indulgence and the transience of earthly pleasures, paralleling his own hedonistic tendencies.

Influence of His Social Circle

The artist’s interaction with various societal groups, from street brawlers to noble patrons, enriched his symbolism. Characters in his paintings often possess a gritty realism, indicating his preference for ordinary people as models, reflecting the seamy aspects of his existence.

Caravaggio’s personal struggles and lifestyle intricately informed his symbolism, adding layers of meaning to the dramatic narratives portrayed in his art.

The Influence of Caravaggio on Subsequent Artists

Caravaggio’s revolutionary techniques and dramatic use of light and shadow had a profound impact on many artists who followed him. His approach departed from the meticulously detailed and idealised forms of the High Renaissance, ushering in a new era characterised by realism and emotional intensity.

Influence on Baroque Artists:

Peter Paul Rubens: Rubens admired Caravaggio’s dramatic compositions and intense realism. He incorporated Caravaggio’s emotional depth and dramatic light into his own works, amplifying the dynamic movement and vibrancy of Baroque art.

Artemisia Gentileschi: Gentileschi’s work reflects Caravaggio’s influence in her use of strong chiaroscuro and realistic, often violent depictions of biblical scenes. Her paintings are notable for their dramatic intensity and emotional power.

Diego Velázquez: Velázquez adopted elements of Caravaggio’s style, including his use of naturalism and direct observation from life. His compositions often feature the same sharp contrasts between light and dark, creating a powerful sense of realism.

Impact on the Caravaggisti:

Orazio Gentileschi: Gentileschi, father of Artemisia, was one of Caravaggio’s early followers. His works often exhibit the same dramatic lighting and realistic detail that characterise Caravaggio’s paintings.

Giovanni Baglione: Initially critical of Caravaggio, Baglione eventually incorporated elements of Caravaggio’s style into his own works. He adopted the dramatic tenebrism and lifelike portrayals that became hallmarks of Caravaggio’s influence.

Jusepe de Ribera: Ribera’s paintings also reflect Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and shadow. His works often depict the raw and human aspects of his subjects, emphasising their physical and emotional reality.

Caravaggio’s Legacy:

Caravaggio’s pioneering use of chiaroscuro made a lasting mark on Western art. His ability to convey extreme emotional states through dramatic lighting set a new standard. His realistic approach influenced not just painters, but also other visual arts, including sculpture and theatre set design.

Caravaggio’s influence extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping the development of Baroque art and inspiring generations of artists who sought to capture the intensity and immediacy of human experience in their work. His innovative techniques continue to be studied and admired by contemporary artists and art historians alike.

Caravaggio was the other Michelangelo of the Renaissance; the two shared a first name but forged different paths.

Angelica Aboulhosn1

Controversies and Conflicts: Multiple Interpretations of Symbolism

Caravaggio’s artworks have often been mired in controversy due to varying interpretations of their symbolism. Scholars and critics sometimes clash over the meanings embedded in his paintings.

Contrasting Interpretations

Different schools of thought have emerged concerning Caravaggio’s symbolic intentions:

Religious Symbolism vs Secular Elements: Some experts argue that certain paintings, like The Calling of Saint Matthew, primarily convey religious values. Others identify secular undertones, such as depictions of everyday life and human struggle.

Innocence vs Corruption: Recognised symbols such as the apple, often associated with innocence, have been debated. In Caravaggio’s works, this element has been linked to corruption and moral decay, creating interpretive conflict.

Naturalistic vs Allegorical: Caravaggio’s commitment to realistic imagery often blurs the line between straightforward representation and deeper allegorical meaning, complicating symbolic interpretations.

Specific Painting Disputes

The Conversion of Saint Paul:

Some analysts see the dramatic portrayal as a clear spiritual epiphany. Others argue that the light and shadow play suggest inner turmoil rather than divine revelation.

Judith Beheading Holofernes:

Judith’s expression and demeanour are seen by some as a symbol of divine justice. Conversely, others view the scene’s brutality as an indictment of self-righteous violence.

Social and Political Contexts

Caravaggio’s paintings are also analysed through the lens of their historical backdrop:

Counter-Reformation Influence: The Catholic Church’s aim to inspire piety and reclaim followers during the Counter-Reformation is perceived in Caravaggio’s religious portrayals.

Personal Life Implications: Caravaggio’s tumultuous personal life, marked by legal troubles and violent incidents, is thought by some to reflect in his art’s darker tones and complex symbolism.

Conclusion of Conflicts

Although Caravaggio’s symbolic use in art continues to spark debate, these discussions highlight the rich layers and profound impacts of his works. The myriad interpretations ensure that Caravaggio remains a pivotal figure in art history, eternally subject to analysis and admiration.

Case Study: Dissecting the Symbolism in ‘The Calling of Saint Matthew’

Caravaggio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew” serves as a rich tapestry of symbolic elements and themes. Painted between 1599 and 1600, this masterpiece can be found in the Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. Each character and object depicted in the painting carries profound meaning.

Light as a Divine Call

Ray of Light: A strong beam of light emanates from the top right corner of the composition. This is widely interpreted as a symbol of divine intervention, guiding Matthew towards his spiritual calling.

Chiaroscuro Technique: Caravaggio brilliantly employs chiaroscuro, creating dramatic contrasts between light and dark. This technique underscores the moment of spiritual awakening and the clarity that divine guidance brings.

Gesture and Expression

Jesus’ Hand: Jesus points towards Matthew with an outstretched arm, his finger mimicking the hand of God in Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam”. This gesture signifies the act of calling and divine selection.

Matthew’s Reaction: Matthew appears astonished, pointing to himself as if to ask, “Me?” His reaction encapsulates human doubt and the shock of being singled out for a higher purpose.

Characters and Attire

Tax Collectors: The figures surrounding Matthew are dressed in contemporary clothing, which contrasts starkly with the timeless robes of Jesus and Saint Peter. This juxtaposition may symbolise the temporal nature of earthly wealth against eternal spiritual riches.

Matthew’s Discipleship: Matthew’s attire is halfway between the contemporary and the ancient, reflecting his transitional state from a life of worldly affairs to one of spiritual commitment.

Symbolic Objects

Coin on Table: The scattered coins signify Matthew’s profession as a tax collector. Their presence juxtaposes the material world against the spiritual calling.

Open Window: An open window in the background functions as an allegory for new opportunities and divine enlightenment.

Spatial Arrangement

Table as a Border: The table delineates the space between Jesus and the tax collectors. This thematic barrier separates the divine and mortal realms, emphasising the transformative power of Jesus’ words.

Depth and Perspective: The linear perspective draws the viewer’s gaze directly to the central action, guiding visual focus while enhancing the painting’s three-dimensional space.

Caravaggio’s “The Calling of Saint Matthew” ingeniously interweaves these elements, forging a complex narrative that invites contemplation and analysis. Through light, gesture, attire, objects, and spatial techniques, the painting subtly conveys themes of divine intervention, transformation, and spiritual awakening.

The Legacy of Symbolism in Caravaggio’s Artwork

Caravaggio’s legacy in the realm of symbolism is prominent, marking a transformative period in the art world. His use of symbolism extends beyond mere decoration, serving as a profound means of storytelling and conveying complex messages.

Religious Symbolism: Many of Caravaggio’s works are steeped in religious iconography. In “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” the use of light signifies divine intervention, illuminating Matthew amidst the shadows, symbolising his spiritual awakening.

Human Condition: Caravaggio often illustrated the human state through symbolic representation. In “The Supper at Emmaus,” the still life of the basket of fruit teetering on the edge of the table signifies the precariousness of life, while the moment of recognition encapsulates the presence of faith and revelation.

Naturalism and Reality: Departing from idealism, Caravaggio’s naturalism conveyed deeper symbolic meanings. “Boy with a Basket of Fruit” includes fruits that show blemishes and decay, symbolising the transient nature of youth and beauty. This candid portrayal challenges the more romanticised depictions of the time.

Light and Dark: His dramatic use of chiaroscuro, the contrast between light and dark, serves as a metaphorical tool. In “Judith Beheading Holofernes,” the stark light on Judith juxtaposed against the darkness enveloping Holofernes’ severed head symbolises purity and justice triumphing over evil and corruption.

Use of Space: Caravaggio’s careful composition often involved spatial symbolism. “The Conversion of Saint Paul” showcases the figure of Paul in a constrained space, signifying his inner turmoil and subsequent spiritual rebirth.

Inverted Symbols: In “David with the Head of Goliath,” Caravaggio includes his own likeness on Goliath’s severed head, possibly symbolising his personal demons and remorse. The inversion of victory and terror paints a complex narrative of the artist’s internal struggle.

Portals to Virtue: In his painting “Saint Jerome Writing,” Caravaggio utilises the skull prominently on the desk symbolising memento mori, a reminder of death that urges the contemplation of mortal life’s fleeting nature, hence implying the wisdom and virtue derived through scholarly pursuit.

Caravaggio’s symbolism continues to spark interest and resonates through time, offering insights into human nature, moral struggles, and divine intervention. His innovative techniques, coupled with layered meanings in naturalistic settings, ensure that his artwork remains a subject of fascination and study.

Conclusion: The Enduring Enigma of Caravaggio’s Symbolism

The symbolism in Caravaggio’s art endures as an enigma, inviting continuous exploration and scholarly debate. Caravaggio, known for his revolutionary naturalism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro, infused his works with complex symbols. These symbols often intertwine:

Religious iconography: His art features vivid religious symbols, such as in “The Calling of Saint Matthew.”

Figures like Matthew and Jesus are depicted with subtle yet profound gestures and expressions, hinting at deeper spiritual narratives. Objects like lanterns and crosses serve as focal points, reflecting his thematic preoccupation with light and redemption.

Human Emotion and Drama: Caravaggio’s characters often convey intense emotional states.

Through detailed facial expressions and postures, he captures moments of psychological intensity, such as in “Judith Beheading Holofernes.” This emotional depth underscores the human experiences of fear, triumph, and divine intervention.

Contemporary References: Incorporating elements from his contemporary world, Caravaggio’s paintings offer nuanced insights.

Use of everyday objects and settings makes the sacred narratives resonate with his audience. His depiction of biblical scenes in ordinary, relatable environments bridges the gap between the divine and the mortal.

Symbolic Ambiguity: Ambiguity in his symbols compels viewers to delve deeper.

This ambiguity invites multiple interpretations, adding layers of meaning and ensuring that his work remains open to varied scholarly perspectives. Caravaggio’s innovative approach to painting and his use of symbolism also reveal a deliberate effort to engage and challenge his audience. By embedding complex symbols and profound themes, he created works that transcend time, continuing to captivate and puzzle viewers centuries later. His art embodies a confluence of technical brilliance and rich symbolic content, marking him as a pivotal figure in the history of art. This enduring intrigue signifies that Caravaggio’s symbolism will remain a fertile ground for interpretation and appreciation for generations.

- Aboulhosn, A. (n.d.) “Caravaggio Was the Other Michelangelo of the Renaissance“. Humanities, The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

https://www.neh.gov/article/caravaggio-was-other-michelangelo-renaissance ↩︎